Guerrillas of new wave humour

But now it’s 1980, and we meet with a little success.

Dexy’s Midnight Runners are top of the charts with ‘Geno’. I’m in Soho, and I feel like I belong. This is a new feeling. I’m a full-time professional comedian and I have a ‘place of work’. ‘No, I’m not being flash, it’s what I’m built to do.’

There are articles in groovy magazines that suggest that Rik and I are at the cutting edge of what they’re calling ‘alternative’ or ‘new wave’ comedy. These are terms that are thrust upon us, we have no hand in making them up. We’re not sure how revolutionary we really are, but we’re very happy to go along with it: we’ve spent the last few years doing rubbish temping jobs trying to earn enough money to allow us to perform at the weekends. I’ve been filling car batteries with acid, working in a pork pie factory, and in the stationery and photocopying department of an international bank. But now we’re doing a show every night, in a club that we’ve set up with some like-minded comedians. It’s called the Comic Strip Club.

I blithely write ‘we’ve set up’ when actually the prime mover is undoubtedly Pete Richardson. He’s the one who thinks we’re all different and that we need our own venue, our own showcase. He’s one of us – he’s a performer – but he’s also the one who’s arranged financial backing from theatre impresario Michael White and the Pythons’ film producer John Goldstone to set up the club.

The main upshot being that we’re being paid to be comedians. Full time. That’s the real revolution.

Walker’s Court is the liveliest and most brightly lit alley in the area, and also the seediest. A passageway between Berwick Street and Brewer Street, it’s at the heart of what’s called the Red Light District. It’s full of signs: Peep show; Model 1st Floor; Non-stop striptease; Live Bed Show; Nude Encounter; Table Dancing; Sex Aids (sadly ironic considering what’s coming), and in the evenings it smells of rotting veg from Berwick Street market; the traders leave whatever they can’t sell lying in the street. Bruised cabbages become footballs for the pissed-up stag parties looking for Amsterdam on the cheap.

Heavy-looking bouncers lend an air of theatrical menace to the scene. They’re dressed anachronistically in sixties suits and hats because they’re part of the show. They’re not there to stop the wrong sort of people going in. They’re there to stop them coming out, or to stop them kicking up a fuss when they’re forced to buy small tins of Heineken at extortionate rates during the purposely long wait for whichever form of mild titillation they think they’ve paid for. This is the scam, this is where the sex joints make their money. But the bouncers know me now, and they smile at me because I’m part of the scene – I’m working at The Comic Strip.

‘Evening, Vernon, evening, Ray,’ I shout.

‘Evening, Nigel,’ they shout back.

Well, perhaps they don’t know me as well as I think they do, but at least they think they know me.

Our club is in the Boulevard Theatre, one of two small theatres inside the Raymond Revuebar which takes up most of the western side of the alley. The other theatre still does strip shows, twice nightly, at 8 and 10. On the wall at the Brewer Street end of the alley there’s a huge backlit sign which reads ‘The World Centre of Erotic Entertainment’, ‘Festival of Erotica’, and more importantly, ‘Fully Airconditioned’. And then, down near the entrance, a much smaller poster in a glass frame proclaims The Comic Strip Club with the strap-line: ‘Guerrillas of New Wave Humour’. Guerrillas. Not Gorillas. None of us really know what it means, but it’s from a review and we interpret it as a sign that we are as hip as Che Guevara, and he’s never been out of style during our lifetimes, so that’s good enough for us.

The two theatres share the same bar, which makes for a diverse crowd, and the outrageously expensive drinks are served by topless barmaids. For an alternative comedian this is called having your cake and eating it.

At one end of the bar sits Paul Raymond himself, the self-styled ‘King of Soho’, famous for publishing a string of porn mags – Men Only, Escort, Club International. As a sixth former I was one of his chief customers. He looks like Peter Sellers doing an impression of a porn baron: he’s wearing fur, he’s got long shaggy hair and a moustache, and he’s dripping with gold, with so many heavy rings on his fingers you wonder how he’s able to lift his drink. But he’s friendly and affable, and he always says hello as we walk through the bar to the backstage area. We very rarely order drinks from the topless barmaids because, even though we like breasts, and even though we’re working full time, we simply can’t afford the prices.

The boys’ dressing room stinks; it stinks mostly of the two suits Rik and I have acquired as our stage gear. We bought them from a stall in Peckham. The bloke said they were made of wool, but I know my wool, and this definitely isn’t wool, it’s some kind of heavy plastic masquerading as wool. The material is about half an inch thick, and as soon as we put them on we start to sweat profusely. They’re mostly purple with strange black squiggles and stripes. We want to look ‘crap’, but as if we’ve made an effort; we want to look like unsuccessful cabaret artistes – and I think we often succeed in more ways than one.

Beneath the suits we wear bright red shirts, and these are probably the biggest problem: they’re cotton and obviously soak up the sweat with ease, so by the time we come off stage they’re wringing wet – literally. We just wring them out. We never take them home. We never wash them. We simply wring them out and put them on hangers to ‘air dry’. When we arrive each evening they are indeed bone dry, brittle almost, with huge white tidemarks of dried sweat, as if they’ve been tie-dyed with bleach. It takes some effort and not a little scratchy discomfort to force them on; sometimes we hear a ‘crack’ as ribbons of salt give way, but within a few minutes of donning the suits the new sweat makes them soft and pliable once more – it’s a foolproof system.

The boys’ dressing room is like our own private club. And this is a new feeling too. It’s fairly small, about ten foot square, with two sinks and a costume rail. But it’s ours. It belongs to us. It’s the first time we’ve had a dressing room – before this we’ve always changed in the toilets or the kitchen. It’s another revolution. It’s our professional home. We’re not students or amateurs any more.

We load the sinks with ice from the machine down the corridor and fill them with the beer we bring in. Whilst the punters are paying through the nose, we each bring in a ‘four pack’ of lager – four cans held together with one of those annoying plastic ring things – which cost about a quid a pack. The ‘four can’ show is the template: two for the first half, and two for the second, perhaps saving the last for post-show before going on somewhere else. It’s deemed a badge of honour to bring in the cheapest four pack, with extra points for the most ridiculous name: Kestrel, Kaltenberg, Charger, Heldenbrau . . . It’s 1980 and there’s a race to the bottom amongst British lager brewers at the moment, but we’re young, full of antibodies, and it gets us to the right level. See? Revolution’s easy once you’ve got yourselves organized.

The regulars in the boys’ dressing room are Rik and myself; Pete and Nige; Alexei; and Arnold Brown, a chartered accountant by day who makes great play of being both Scottish and Jewish – ‘Two racial stereotypes for the price of one’. Arnold isn’t a big drinker so the two sinks basically hold twenty cans of beer. We have occasional guests: the Americans rarely drink, generally preferring less-fattening stimulants; semi-regulars like Ben Elton know to bring their own cans; and the others we don’t really mind offering to as long as they’re amusing.

I know Ben from the Manchester University Drama Department, though he was a couple of years behind me. He’s a prolific gag writer, a hilarious social commentator, and has the wiry enthusiasm of a terrier puppy. Our relationship, and that of our two families, grows over the years into a thing of great depth and wonder, though – as a man who’s always keen to win – he’s never got over the fact that whilst playing for the final ‘cheese’ in a game of Trivial Pursuit he once had to ask me, ‘Who played Vyvyan in The Young Ones?’.

The dressing room next door is where the latest double act to join the group, French & Saunders, share a less drink-based evening with the house band – Simon Brint, Rod Melvin and Rowland Rivron. Pete worried about not having any women on the bill so auditioned some female acts, and their room is called the girls’ dressing room even though it’s 60 per cent male.

Dawn and Jennifer have a range of sketches from a Dolly Parton parody – a twosome country act called The Fartons – to the Menopazzi Sisters, two wannabe circus daredevils in black leotards with nipple tassels on the back, who are incredibly cowardly and unadventurous – a leap of six inches is treated as a great feat of derring-do. Hired to address the gender balance, they are incredibly funny and by no means a token – and they go on to be the most successful out of the whole group.

Dawn is still a full-time teacher when she starts at the club and she brings a little of the schoolteacher with her – she’s organized, likes things to be done properly, and is not averse to telling people off if she thinks they’ve misbehaved. Jennifer is just the coolest person on the planet.

Simon and Rod are rather effete, they’re slightly older than us and have experience of living in the sixties – they have a seductive experimental edge about them. Simon and I invest in an eight-track reel-to-reel tape recorder together, and we keep it in his flat, so I’m always round there. We become very close.

Rowland, the drummer, is hard to know when he first arrives. He’s recently been punched in the face by a complete stranger in the street. This broke his jaw, which has been wired together until it heals. He drinks protein shakes through a straw and can’t say much. Once the wiring is removed he never stops talking. We spend a large part of the early eighties playing pool together in The Royal Mail in Islington. We become such regulars that we can leave our unfinished drinks on the pool table when the pub closes at three and pick them up again when we come back at five.

The dressing rooms aren’t exclusive by any means, people flit between the two, but the boys’ room is always a bit rowdier, and the girls’ more calm. You can go wherever your mood takes you. Alexei’s wife Linda is a permanent fixture in the boys’ dressing room, always slightly drunk, and always haranguing us for being too middle class to have an opinion.

Alexei and Linda are very keen on telling everybody, every day, every hour, that they are working class. No matter what the conversation is about – politics, art, football, knitting, koalas, a paper-cut – they are both of the opinion that their opinion is the true opinion, because they’re working class.

Rik and I often play a game to see which of us can make them say it first. In the same way that if you mention snow someone will say that the Eskimos have fifty different words for it, or if you mention swans someone will be unable to resist telling you that a swan can break a grown man’s arm with one flap of its wing, if you adopt any kind of political stance in the presence of Alexei and Linda they will tell you that you’re too middle class to have an opinion.

The Comic Strip Club runs for a year and I remember it as a year-long party. The regular acts basically do a ten-minute spot in each half, Alexei compères, and the guest act does whatever it does.

There are lots of guest acts: there’s a Peruvian nose-flautist; there’s a man who pretends to be a trumpet. There’s an act called Furious Pig, I don’t know what they’re trying to do but there are a lot of them, they have circus skills, and they’re furious. Being furious is very much in vogue, the act Rik and I have involves a lot of swearing, shouting and violence; everyone’s going berserk. Alexei looks like a psychotic bouncer and likes to frighten people; Keith Allen occasionally shows up and aims to be provocative – he’s very angry about something though no one can ever quite tell what (maybe this is making him even angrier) – he’s very hit and miss, though always exciting to watch, the failures sometimes more exciting than the successes. There’s the brilliant night that Robin Williams turns up late, goes straight on in the second half and does material that Chris Langham has already done in the first – we never find out who the original stuff belongs to.

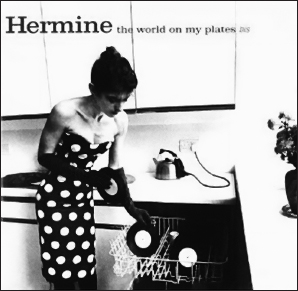

But my absolute favourite is Hermine.

Hermine Demoriane is a French chanteuse with the artful, vaguely out-of-tune style of Nico from The Velvet Underground. She sounds like a drugged-up Marlene Dietrich. She’s also a performance artist and an occasional tightrope walker. It pays to diversify. She’s aloof, and a bit scary, but fascinating to watch, and she only ever sings one of two songs: ‘Veiled Women’ or ‘Torture’.

Her album has a photo on the front of her wearing a cocktail dress and stacking a dishwasher with vinyl singles. It’s a photo that amuses me every time I see it. Simon Brint, who played piano and organ on the album (maybe it’s Simon that’s buying all the ‘organ and vocals’ books) has the poster for it in his flat and I study it every time I go round. It’s an image that sticks with me – a very ordinary situation subverted.

Her performances at the Comic Strip Club usually see her go on stage wearing an enormous cone of newspapers that have been stuck together. As she sings she sprays herself with paint from an aerosol, and then fights her way out as the song comes to a close. There’s always some insecurity about the performance, it teeters on that delicious line between success and failure.

The Comic Strip Club gets a lot of attention. A lot of famous types turn up to see us: Jack Nicholson, Dustin Hoffman and Bianca Jagger come on the same night. It’s front page news in The Sun the next day as BIANCA’S FOUR LETTER NIGHT OUT. It only has 200 seats but the club punches above its weight because it’s the only one of its kind.

Is it revolutionary? Are we revolutionary? In one way, yes, because there’s nothing else like it at the time. I suppose that’s the definition of revolutionary.

We’re certainly very different from the dinner jacket and bow tie brigade that still dominate the world of live comedy in the working men’s clubs at the time. There hasn’t been a club like ours since The Establishment – the club Peter Cook opened round the corner in Greek Street at the height of the satire boom, but that closed in 1964. Nor are we the clever darlings of the Cambridge Footlights. Our red-brickness is the true revolution, the true point of difference.

There’s a lefty political edge to all the performers at the Comic Strip, and not just Ben making jokes about ‘Thatch’, but a generally socialist view of the world.

How do you make the joke about a gooseberry in a lift left wing?

Fair point. It’s true we never identify the politics of the gooseberry. But sometimes the politics is in what you don’t do rather than what you do do.

‘Non-sexist and non-racist’ is the overarching battle cry, though Rik and I joke that perhaps it should be ‘Non-sexy and non-racy’; in the same way, we often interpret ‘Alternative Comedy’ as ‘Alternative to Comedy’.

As you can see, I keep subverting the proposition, and not through some kind of false modesty, or reluctance to be thought revolutionary – who wouldn’t want to be revolutionary – but fundamentally because I see our double act as part of a line going back through Pete & Dud, Morecambe & Wise, and Tom & Jerry, all the way to Laurel & Hardy.

Though if you ask me if I’ve seen an act as berserk as ours before or since, I would have to say I have not.

Perhaps the marker of how revolutionary it is is the number of copycat clubs that spring up after it – after a few years an entire ‘circuit’ develops – and in that way alone it’s at the forefront of a revolution in comedy.